From War to Peace – Yoga for the Management of Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder

Swami Ahimsadhara Saraswati (Helen Cushing), Satyananda Yoga Centre, Hobart, Australia

Let me introduce Swami Atmadhyanam. Many simply know him as Terry. Terry used to think of himself as a Vietnam War veteran. Now he thinks of himself as a yoga teacher and sannyasin. The years between Terry’s 11 months in Vietnam (1968) and the time he embraced yoga (1992) read like a textbook case of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). He recalls, “I was in the pub when it opened and I was the last one to leave when it closed. I was taking 30 Valium a day. When I couldn’t sleep at night I’d get up and have a coffee and cigarette. If the hose kinked, I’d get an axe and chop it up. If the lawn mower stalled, I’d throw it over the fence. I don’t know how I functioned. Yoga saved my life.”

Atmadhyanam’s journey from war to peace was guided by his yoga teacher, the late Swami Hari Saraswati. He was one of a group of Vietnam veterans and their partners whom she taught for 12 years. When Hari could no longer teach due to illness, she asked me to work with the veterans.

About PTSD

Post-traumatic stress disorder is defined as an anxiety disorder. It can occur following experiences that are extremely frightening, threatening and traumatic. Intense failings of fear, helplessness and horror are generally involved. While most trauma survivors exhibit short-term psychological reaction (acute stress disorder), some develop long-term, serious problems, showing that the body has failed to return to its pre-traumatic state.

Historically PTSD was most commonly recognised in soldiers during and after battle – previously known as ‘shell-shock’ and ‘battle fatigue’. As understanding of the condition has developed, its wider occurrence has been acknowledged. Survivors of serious accidents, natural disasters, rape, robbery and torture are vulnerable, as well as people who witness a deeply disturbing event, i.e. emergency personnel, police and prison workers or the driver of a car that hits a pedestrian. PTSD is even experienced by people who have been subjected to prolonged psychological victimisation. As such, PTSD is a condition affecting a wide range of groups and individuals within society.

Symptoms of PTSD

PTSD is a multi-layered condition with a range of long-term symptoms that prevent people from coping with life. They may not arise until years after the trauma if the person strongly represses the feelings associated with the trauma. The occurrence of symptoms is often unpredictable and erratic, undermining a person’s knowledge of themselves, their identity and their own trust in their ability to function reliably at work, in relationships, and in society in general.

The symptoms of PTSD are categorised into three groupings:

- Re-experiencing the trauma: flashbacks, nightmares, recurrent thoughts and emotions about the trauma, panic attacks.

- Avoiding situations/feelings that might trigger the memory: self-protection by emotional numbing/flatness/reduced range of feeling, repressed memory, social isolation, distancing from those who are close, sense of hopelessness about the future resulting in depression and inability to act.

- Constant state of high arousal: always on the alert, hyper-vigilant, overreaction, irritable, jumpy, sudden intense anger, lack of concentration, overly suspicious, guarded, insomnia.

Added to these debilitating, out of control reactions there is often painful guilt about both past actions and continuing dysfunction in the present, which is especially prevalent in war veterans.

Self-medication through abuse of prescription medication, alcohol and illegal drugs, not to mention excessive caffeine and tobacco intake, brings another layer of complexity and tragic outcomes to the lives of sufferers and those around them. Suicide, whether through the conscious taking of one’s own life or through ongoing self-destructive behaviours, may feel like the only path to relief.

The yogic point of view

From the yogic point of view, PTSD is a state of extreme disconnection. The body, mind and emotions are perceiving and functioning in a way that has no connection to the present. A stagnation of mind has occurred. Ongoing, inappropriate physiological, mental and emotional reactions cause havoc with the subtle energy system and in this muddle we move further from, rather than closer to, the harmony of body and mind which guides us towards integration and connection with spirit.

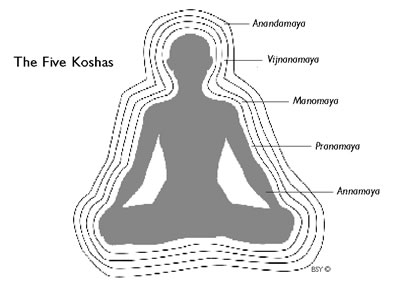

The breadth and integration of techniques, philosophies and lifestyle which are hallmarks of Satyananda Yoga make it particularly effective in helping a condition as complex as PTSD. Theoretically, the yogic physiology of the koshas gives a useful basis for understanding the disintegration of personality inherent in PTSD. Each of the koshas may be in a state of crisis.

Annamaya kosha

Annamaya kosha, the physical layer, is jagged with muscular tension and nervous and endocrinal system overload. A multitude of bodily ailments follows. Before the first yoga class, each newcomer to the Vietnam Veterans group fills out a health questionnaire. I have never seen so many boxes ticked – digestive problems, arthritis, back and joint problems, hernia, recent surgery, tinnitus, and high blood pressure, as well as the expected psychological difficulties, including insomnia, headache, depression and anxiety.

For direct healing and support of annamaya, the yogic prescription of asana is simple, accessible and cheap. The effects are both immediate and cumulative. Relaxation is also an important practice for annamaya. The need to release deep muscular tension cannot be overstated for people with extreme and chronic tension.

Diet and the state of annamaya kosha are directly related. One of the things the veterans look forward to when we go on a retreat is the delicious vegetarian food. Many of these men are divorced and often they live alone, as PTSD is destructive to relationships. The lifestyle encourages reliance on convenience foods such as takeaways and processed meals, as well as comfort eating. In a comprehensive program the role of a healthy diet can also be taught.

Pranamaya kosha and the breath

Pranamaya kosha, the energy body, is intertwined with the breath at the physical level, the quality of breathing reflecting the state of the body, mind and emotions. In the person suffering from PTSD, pranamaya kosha is contracted. To contract the breath and prana brings suffocation of flow. The person’s energy is unpredictable and has difficulty flowing with the river of life. The muscular tension blocks the nadis and restricts the breath. The mental and emotional tightness blocks the flow of knowledge and feeling into appropriate action, resulting in panic, anger, suppression, isolation, breakdown, insomnia or stress. The high state of arousal means unevenness and struggle in pranamaya kosha.

Asanas play a vital role in clearing blockages to the flow of prana in the body. To feel fresh, clear energy pulsing through the body and mind, that is the gift of asana to pranamaya kosha. Yoga nidra and simple pranayama are powerful tools for balancing, harmonising and managing energy. To be able to sleep without pills, without self-medicating on alcohol or marijuana, that is the gift of yoga nidra to pranamaya kosha. The vibration of Om chanting in meditation and the mantra and music of kirtan go directly to pranamaya kosha. They cleanse, they vitalise, and they harmonise.

Manomaya kosha

In the PTSD sufferer, manomaya kosha, the mental and emotional layer, is rife with insecurity, mood swings, fear, defensive reactions, confusion or despair. Of course, these feelings and thoughts are in constant interaction with annamaya and pranamaya. Because of this, the asanas and pranayamas also bring some peace to manomaya. But the most conscious work on manomaya involves direct mind management. Witnessing (which involves detachment), acceptance and letting go are key among these.

To feel difficult emotions successfully (i.e. without destructive reaction), the witnessing aspect must be cultivated. We are learning to reassess and re-create our identity, our self-image, the ‘I’ that we project onto all interactions: the basis of our perception of the world.

This task involves some rescripting of our life story. In the struggling, disjointed world of PTSD, the sankalpa becomes a precious, trusted friend. Here in the personal, private realm of sankalpa you begin to make friends with your mind. Positive, changeless, simple, on-call, the sankalpa shines a light into the deep darkness. Positive experiences in stories and visualisations during yoga nidra also help with this rescripting – taking them on a journey to beauty and serenity. Place these stories deep into their subconscious. Inject positive samskaras into the mind.

Meditation is generally recommended for harmonising and strengthening manomaya. For PTSD sufferers, many meditation techniques are out of reach. To watch the thoughts in antar mouna will be a huge challenge. To witness images in chidakasha invites flashbacks in a state of isolation. To simply sit still and close the eyes is a big task in the beginning. A wise approach to the benefits of meditation is to balance the internalisation with some sensory input. Trataka and Om chanting offer this type of reassurance. Meditation practices that are non-intellectual, simple and foster connection to reality will help heal the shattered manomaya of PTSD.

Practices for easing PTSD

I start each class with the ‘tense and release’ series as follows: Lying in shavasana, starting with the right hand, take the mind there and inhale while creating tension. Make a tight fist while breathing in, focus on the feeling, try to isolate the tension in that part of the body only, hold it with the breath, release the hand with the breath. Each body part is tightened and let go three times. Finally, they tighten the whole body at once: the arms, legs and head lift off the floor as the muscles are consciously tensed. As the breath is let go the head and limbs flop back down with release and relief.

Asanas:

- These simple asanas form an excellent basis:

Pawanmuktasana (PM) 1, supta udarakarshanasana (sleeping abdominal stretch), marjari-asana (cat stretch) (left), shashankasana (child pose), makarasana (crocodile), simhagarjanasana (roaring lion), tadasana (palm tree), tiryaka tadasana (swaying palm tree) and kati chakrasana (waist rotation). - It is wise to go easy on the PM2 as high blood pressure and bad backs are common. Modifications such as bending the passive leg make the simpler PM2 practices available. From PM3, chakki chalasana (churning the mill) and nauka sanchalasana (rowing the boat) are energising, strengthening and benefit the prostate.

- Hasta utthanasana (hand raising) and eka pada pranamasana (one-legged prayer pose) (right) add a graceful dimension, nourish anahata and foster concentration and steadiness.

- Within the asana practices are breath regulation and awareness, subtly adding depth to the influences of the asana.

Pranayama:

- Remember Atmadhyanam’s fits of anger? With the help of simple breathing techniques he learned to manage those surges and impulses. For anger management, Atmadhyanam’s yogic formula is:

- Big W for Witnessing + ujjayi + full yogic breath + extended out breath = calm outcome and peaceful living

- These simple breaths can be called on anywhere, at any time of day, as well as practised routinely during sadhana. They are tools for short-circuiting a crisis. Bhramari and simple nadi shodhana cannot be practised on the spot to quell fires of raging emotion, but are valuable in classes and sadhana.

Yoga nidra:

- Psychiatrist Dr Rishi Vivekananda, who has worked with Vietnam veterans in his practice, believes that yoga nidra saved many of them from suicide. Yoga nidra was one of the most important techniques in transforming Atmadhyanam’s life. Insomnia was his major problem. Terrifying nightmares, sweats and flashbacks fractured his nights. He decided to substitute yoga nidra for the coffee and cigarettes. Each night he would go to sleep to a yoga nidra tape. When he woke, he pressed the button again. He might do this six times in one night. This process went on for about three months until he found that he stayed asleep and the button was out of a job. He had retrained his mind, his body and his energy with persistence and commitment. Other practices and changes no doubt supported the process.

- Even with yoga nidra, however, the approach must be flexible and simple. In a state of arousal and hyper-vigilance, pratyahara is difficult. As I look around a group of veterans lying in shavasana, many of their palms are pressed down or arms are folded across their body. The legs often end up crossed as well. Eyes stay open for a long time. I watch as one veteran with very little flexibility seems to do more PM1 during yoga nidra than in the asana session. His feet and hands are often on the move, twitching, restless, perhaps ready for action. The veterans like visualisations that weave a story, taking them to a peaceful place. It is as though this process helps them to recreate their own story, replacing the images of war, loss and futility.

- The deep effect of sankalpa has already been mentioned, but just as we repeat it during yoga nidra, it’s worth repeating here. One-to-one time spent developing a sankalpa not only helps the process at a practical level but fosters trust and connection between teacher and student which, in itself, is therapeutic.

Meditation:

- Trataka was Atmadhyanam’s number one practice for transformation. “When I first did trataka the flashbacks started. I said, no way, I’m not doing that anymore. Hari encouraged me. She helped me detach from the experiences, watch them without involvement. Gradually they lost their grip. Then they stopped coming.” I like to think of that small bright flame in the dark, burning up the pain and transferring its steady light. In trataka the object of concentration is a concrete point of reference – something real and stable for a mind beset by unreality and instability.

Om chanting is also useful. In a class, there is a group dynamic involved, as well as a physical process and a sound/vibrational input. At home alone, the sound is a companion. While for many of us the chanting of Om is infused with tradition, esoteric meaning and philosophical beauty, the actual production and vibration of Om is not abstract. It is very real for people with PTSD who need positive experiences of reality.

From soldier to yogi

I have presented some yogic practices and concepts that can help relieve the physiological and psychological load of PTSD. Much more could be written, exploring the role of karma yoga and bhakti and seva in particular. In the journey that transformed Terry into Swami Atmadhyanam these have been vital. They integrate the experience of life, directing consciousness into the two remaining koshas – vijnanamaya and anandamaya, the realms of connection with higher consciousness and spirit. A foundation for steady healing, however, exists in the simple techniques outlined here. They are accessible to all who wish to move out of stagnation and into flow, out of disconnection and into connection, out of dark despair and into the light of purpose and joy.