Yogic Lifestyle and Subjective Wellbeing

John Thomas (Sannyasi Dharmadev)

Abstract

Personal wellbeing has been conceptualized as optimal functioning rather than merely absence of pathology. Research into wellbeing has centred on the term subjective wellbeing (SWB), measured by overall satisfaction with life and by satisfaction across various life domains. While SWB is considered to remain relatively stable over the lifespan, life events, including relationships, belonging, progress towards life goals, a sense of purpose in life and health have an impact. The degree to which one experiences control over one’s response to life events (perceived control) is considered to have a buffering effect for adverse life events and may enhance wellbeing. Perceived control may be a factor in the role of spirituality in wellbeing and may enhance one’s sense of purpose in life. Major domains for life satisfaction are positive relationships, health status and achievement of life goals.

Yoga is finding acceptance in the West not just as a means to health and fitness, but increasingly as a holistic life philosophy and a spiritual path. It is hypothesized that yoga’s effect on SWB results from its impact on health, purpose in life (spirituality) and perceived control. Yoga practices are aimed at personal growth rather than improvement in relationships.

This study was undertaken to examine the relationship between adoption of a yogic lifestyle with measures of SWB and perceived control of internal states in a cross-sectional sample of Australian yoga students. Students undertaking intensive Yogic Studies training scored higher on both wellbeing and yogic lifestyle measures than yoga students attending a weekly class. They also had higher scores on perceived control, supporting the view that self-awareness or perceived control may enhance SWB in the personal sphere. Adoption of a yogic lifestyle showed a moderate correlation with life satisfaction in the domains of spirituality and health, but a lower correlation with satisfaction with relationships.

Introduction

Diener (1997) has defined subjective wellbeing (SWB) as ‘how people evaluate their lives’. It is considered to be a function of three variables: life satisfaction, lack of negative mental states and the presence of positive mood and emotion. SWB has been measured either as overall ‘life satisfaction’ or ‘quality of life’. As a measure of the former, Diener (1997) has developed the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), a self-report rating on a seven point scale of five statements about life satisfaction. The Personal Wellbeing Index (Cummins et al, 2001) measures quality of life by self-reporting of satisfaction on a ten point scale in the domains of: standard of living, health, achievement, relationships, safety, community and future security, and was also used with an additional domain of ‘religion/spirituality’.

Demographic factors such as age, sex, ethnicity, education and income have been summarized by Diener (2003) as contributing less than 20% of the variance in SWB. Cummins (2002, 2004) has developed a theory of SWB Homeostasis, which proposes a genetically determined ‘set-point’ for personal wellbeing that is internally maintained and defended. A person tends to revert to this set-point as adjustments are made to life circumstances and events. Chronic stress may challenge homeostasis, while positive relationships may strengthen it.

Temperament and personality have been seen as the major determinants of SWB and the reason for its stability over a lifespan (Diener, 2003). Traits frequently associated with high levels of SWB are extraversion and agreeableness (Costa and McCrae, 1992 reported in Ryan and Deci, 2001), while neuroticism has shown a negative association.

Headey and Wearing assert in their book Understanding Happiness that ‘a sense of meaning and purpose is the single attribute most strongly associated with life satisfaction’. They link purpose in life to ‘belonging, in a social, spiritual and personal sense’. For most people, life satisfaction and meaning is derived from their relationships. Diener (2003) considered quality social relationships as necessary for SWB.

Meaning in life has also been related to the setting and achieving of life goals. Diener (2003) reported studies suggesting that progress towards one’s goals ‘is one of the basic predictors of SWB’. Goal achievement gives a basic sense of control over one’s life and can be attributed mainly to personality. A sense of control or perceived control over one’s reactions has been linked with wellbeing as a buffer for adverse life events. Perceived control of internal states has been suggested by Pallant (2000) as a mediating mechanism in the usefulness of various cognitive-behavioural strategies (in which she included yoga) in stress management.

Yogic lifestyle

As Cohen and Penman (2004) note, while yoga’s ultimate goal is ‘the achievement of enlightenment or absolute bliss’, the practices of yoga provide ‘a way to promote wellbeing and treat disease’. Bhushan (1998) describes yoga as ‘a holistic approach to health of which the body, mind and spirit are integral and interdependent parts’. While for many practitioners, yoga remains a gentle form of exercise and relaxation, some are drawn to engage with its teachings at a deeper, spiritual level. When adopted as a spiritual path, yoga can come to underpin one’s entire approach to life.

‘Yogic lifestyle’ is a modern expression of the yogic philosophy of life derived from Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras (raja yoga). It has as its basis the first two of Patanjali’s eight limbs, yama: ethical standards for behaviour towards others, e.g. truthfulness, non-violence, and niyama: guidelines for one’s relationship with oneself, e.g. self-study, contentment. Regular yoga practice is an important component and covers the next five limbs: asana, pranayama and meditation (pratyahara, dharana and dhyana). Yoga practices have the aim of integrating functioning at the physical, energetic, mental and spiritual levels. (Feuerstein, 1975)

Bhushan defines a yogic lifestyle as stemming from a holistic view of life that emphasizes balance and harmony. It espouses simplicity and regularity of lifestyle with balance in diet, sleep, relaxation and activity. Key features are self-awareness and the capacity to witness one’s thoughts, feelings and actions with acceptance and non-attachment. This awareness of one’s response to situations is described as ‘meditation in action’ (karma yoga). A yogic lifestyle can include the bhakti yoga practices of mantra and kirtan, which have been associated with positive feeling states. The hatha yoga practices for internal cleansing complement the other aspects of a yogic lifestyle.

The development of self-discipline is seen as central to a yogic lifestyle. Traditionally, commitment to a life of yoga involved renunciation of worldly attachments, including intimate relationships. However, the ideal suggested for the average householder today is a ‘middle path’ between the extreme renunciation practised by those living in an ashram and the extreme attachment to the material world. While not addressing personal relationships specifically, yogic practices can help to nurture the development of compassion for others. This compassion can extend to concern for the wider environment and ecology of the planet.

Relationship of yogic lifestyle to wellbeing

From the description given above, a yogic lifestyle would seem to impact on a number of the factors associated with SWB. Yoga can be viewed as ‘general health enhancing activity’ (Cohen and Penman) that can be combined with other lifestyle activities to enhance health and wellbeing, e.g. diet, exercise, stress management. When yoga becomes a daily personal practice, it begins to impact on one’s lifestyle, with yogic values of simplicity and balance in daily life attaining greater importance.

When yoga becomes the integrating focus of one’s life, it can provide a sense of purpose and meet the need for a spiritual dimension, either as a life philosophy in itself or in supporting religious beliefs. The extended yoga community can provide a sense of belonging and social support. The long-term aim of regular yoga practice is modification of the personality structure, to enable spiritual transformation.

Bhushan explored the effect of participation in an intensive yoga course (four month residential Certificate Course in Bihar Yoga/Satyananda Yoga) conducted at Bihar Yoga Bharati (BYB) in Munger, India, on measures of psychological wellbeing. He found a significant reduction in scores on Spielberger’s State Trait Anxiety Inventory for those with initial high levels of anxiety, but little change in those with initial low levels of anxiety.

This study

Satyananda Yoga is an integral style of yoga aimed at developing an inner attitude of self-awareness. It incorporates aspects of raja, bhakti, karma and hatha yoga. Classes typically include asana, pranayama, relaxation and chanting. The Yogic Studies modules offered in Australia were developed from the courses offered at BYB in India. They now form the first four semester modules (Yogic Studies 1a, 1b, 2a, 2b) occupying the first two years of the three year Diploma of Satyananda Yoga Teaching. The Yogic Studies modules are designed to instil a yogic lifestyle and the establishment of a regular daily yoga practice routine. Each module commences with a two-week residential stay at a Satyananda Yoga ashram.

This study explores the relationship between measures of yogic lifestyle and indices of SWB in students at various stages of Yogic Studies and students attending a weekly Satyananda Yoga class in the community. Of particular interest are the domains of life satisfaction with ‘spirituality’, ‘health’, ‘relationships’ and ‘community’.

This study consists of:

- Part 1: A comparison of the documented SWB factors with those reported by participants as contributing to their sense of wellbeing and the factors they consider essential to a yogic lifestyle.

- Part 2: It is hypothesized that higher scores on yogic lifestyle measures are associated with higher scores on the SWB scales, and progression through the Yogic Studies modules, and that Yogic Studies students score higher on yogic lifestyle measures than those attending a weekly yoga class.

- Part 3: The relationship between yogic lifestyle and perceived control is explored, with the hypothesis that higher levels of perceived control are associated with greater adoption of a yogic lifestyle with higher scores on wellbeing.

Method

Participants: 152 yoga students (33 male, 119 female) (mean age 39.7 yrs, SD 9.8) took part in the study. They were recruited from those undertaking the Yogic Studies modules at Satyananda Yoga Academy and those attending weekly Satyananda style yoga classes in the community.

Materials: All participants completed the following questionnaires: (1) Wellbeing: Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) (Diener, 1997); (2) Personal Wellbeing Index (PWI) (Cummins, 2001); (3) Perceived Control of Internal States Scale (PCOISS) (Pallant, 2000); (4) Yogic Lifestyle: Personal Questionnaire designed for this study, which included demographic details; yogic experience; regularity of practice and class attendance; importance of yoga as a spiritual, philosophical, practical basis for life; adoption of yogic lifestyle; essential elements of a yogic lifestyle; factors that make up sense of wellbeing.

Results

Part 1: Comparison of factors reported by participants as contributing to their sense of wellbeing and factors associated with a yogic lifestyle with those from the documented SWB indicators.

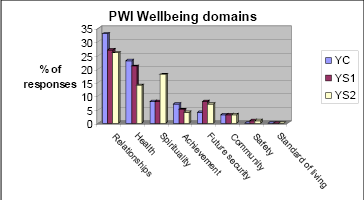

Reported factors contributing to wellbeing: Responses to the open question, “What factors in your life make up your sense of wellbeing?” were categorized where possible into the domains of life satisfaction of the Personal Wellbeing Index.

In decreasing order of frequency, the major factors reported were: relationships (partner, family, friends); health (often holistic health, physical and mental); spirituality (particularly for YS2 students); achievement (particularly in work); future security; feeling part of a community.

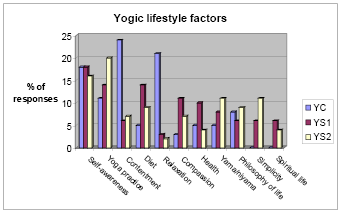

Reported factors contributing to yogic lifestyle: Responses to the open question, “What do you see as the essential elements of a yogic lifestyle?” were categorized into factors reflecting a similar content.

The major factors reported were: self-awareness and self-acceptance; regular yoga practice; followed by lifestyle factors with similar frequency, ranging from contentment to ethical behaviour and values to diet and health.

Part 2: Correlation of wellbeing measures with yogic lifestyle measures.

Correlation of wellbeing measures with yogic lifestyle measures

| Variable | Mean | Std Dev. | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| SWLS | 24.941 | 5.726 | 152 |

| PWI | 7.091 | 1.490 | 152 |

| Y years | 8.362 | 8.235 | 152 |

| Y class | 2.763 | 1.195 | 152 |

| Y pract | 3.500 | 1.352 | 152 |

| Y imp | 6.322 | 1.059 | 152 |

| Y curr | 4.684 | 1.334 | 152 |

| SWLS | PWI | Y years | Y class | Y pract | Y imp | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWLS | 1.000 | |||||

| PWI | 0.781** | 1.000 | ||||

| Y years | -0.138 | -0.124 | 1.000 | |||

| Y class | 0.193* | 0.196* | -0.036 | 1.000 | ||

| Y pract | 0.314** | 0.303** | 0.225** | 0.090 | 1.000 | |

| Y imp | 0.190* | 0.237** | 0.200* | 0.040 | 0.534** | 1.000 |

| Y curr | 0.417** | 0.396** | 0.091 | 0.194* | 0.606** | 0.485** |

Correlation between wellbeing domains and yogic lifestyle

| Y curr | Spirit | Health | Relation | Comm | Safe | Secure | Achieve | Std | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Y curr | 1.000 | ||||||||

| Spirit | 0.385** | 1.000 | |||||||

| Health | 0.383** | 0.319** | 1.000 | ||||||

| Relation | 0.243** | 0.500** | 0.374** | 1.000 | |||||

| Comm | 0.307** | 0.393** | 0.410** | 0.435** | 1.000 | ||||

| Safe | 0.240** | 0.463** | 0.523** | 0.572** | 0.441** | 1.000 | |||

| Secure | 0.244** | 0.446** | 0.486** | 0.597** | 0.451** | 0.593** | 1.000 | ||

| Achieve | 0.334** | 0.406** | 0.580** | 0.518** | 0.527** | 0.449** | 0.506** | 1.000 | |

| Std | 0.366** | 0.436** | 0.458** | 0.508** | 0.467** | 0.490** | 0.601** | 0.555** | 1.000 |

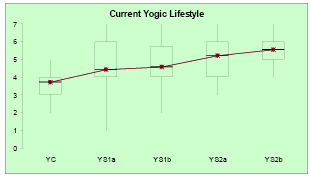

Relationship between Yogic Studies and yogic lifestyle

The Tukey post-hoc test for ‘current yogic lifestyle’ showed YC to be significantly different from YS1b, Ys2a, YS2b at 0.05, and YS1a and YS1b to be significantly different from YS2b at 0.05.

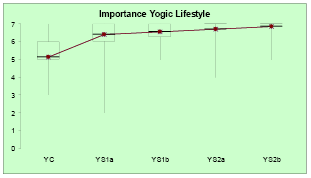

Relationship between Yogic Studies and wellbeing

The distribution of wellbeing measures across the Yogic Studies modules showed that for both measures, the weekly class group had higher wellbeing scores than those in YS1a and YS1b, but the means for YS2a and YS2b were higher than the weekly class group. The dotted line is the population mean for each measure. On the PWI, the YS1a and YS1b groups were below the norm.

Relationship between Yogic Studies and wellbeing domains

The following box plots show the means for the groups across PWI domains.

Satisfaction levels for health, spirituality and community showed a similar pattern, with the weekly class group mean being higher than YS1a and YS1b, but YS2b being higher than the weekly class group. Satisfaction with community was lower than the norm for all groups except YS2b.

The means for all groups on satisfaction with relationships were below the norm except for YS2a, with YS1b being the lowest level of all domains.

Part 3: Relationship between current yogic lifestyle, perceived control and SWB.

Correlation between SWLS, PWI and measures of yogic lifestyle (Ycurr), PWI domain of spirituality, primary control (PWI domain of achievement) and perceived control (PCOISS)

| SWLS | PWI | PCOISS | Y curr | Spirit | Achieve | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SWLS | 1.000 | |||||

| PWI | 0.781** | 1.000 | ||||

| PCOISS | 0.546** | 0.609** | 1.000 | |||

| Y curr | 0.417** | 0.396** | 0.426** | 1.000 | ||

| Spirit | 0.571** | 0.570** | 0.444** | 0.385** | 1.000 | |

| Achieve | 0.687** | 0.783** | 0.473** | 0.334** | 0.406** | 1.000 |

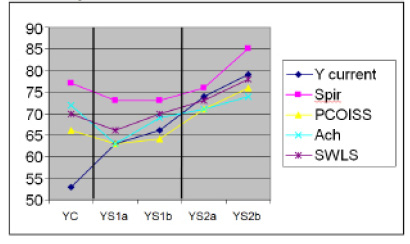

Means of measures converted to % of scale maximum across groups

It can be seen that, for those attending a weekly class, there is disparity between the measures. In YS1a and YS1b the association is closer, and they are closely associated in YS2a and YS2b.

Discussion

Factors of wellbeing and yogic lifestyle: The responses to the open questions about factors contributing to wellbeing indicated that for this sample of yoga students, close relationships were seen as the major determinant of their wellbeing, followed by health and spirituality. Spirituality was mentioned more frequently by those in their second year of Yogic Studies. The open-ended question relating to the components of a yogic lifestyle showed a general understanding of the important aspects of a yogic lifestyle, with an emphasis on self-awareness and self-acceptance, and the need for regularity of yoga practice.

Relationship between yogic lifestyle and wellbeing: The results supported the major hypothesis that higher scores on measures of yogic lifestyle were associated with higher scores of life satisfaction measures of SWB, indicated by a moderate correlation with both the overall measure (SWLS) and averaged over life domains (PWI).

The highest correlation with the wellbeing measures was respondents’ rating of ‘how well their current lifestyle matched that of a yogic ideal’. The next highest correlation was with ‘regularity of yogic practice’. These two factors can be taken to represent the integration of yoga into one’s lifestyle. Their moderate inter-correlation (0.61) reinforces the central role that regularity of practice (more than four days per week) occupies in a yogic lifestyle.

The measure of ‘regularity of attendance at yoga classes’ was weaker in its association with wellbeing measures. This factor showed only a low correlation with ‘current yogic lifestyle’ and so may indicate that attendance at yoga classes does not necessarily indicate the adoption of yoga as a lifestyle. This finding may also reflect the requirement for Yogic Studies students to undertake daily practice, which may reduce their need for formal class attendance outside of their daily practice. Similarly, the low association of ‘number of years practising yoga’ with ‘current yogic lifestyle’ may indicate that the length of time one has practised yoga does not necessarily equate to adoption of a yogic lifestyle.

Yogic Studies and yogic lifestyle: Progression in Yogic Studies modules showed a clear association with higher ratings of ‘current lifestyle meeting the yogic ideal’. Those attending a weekly class gave the lowest self-rating of adopting a yogic lifestyle. In distinction to those attending a weekly class, Yogic Studies students at all levels gave a very high rating to the importance of a yogic lifestyle. This would support the view that enrolment in Yogic Studies indicates a desire to cultivate a yogic lifestyle.

Domains of wellbeing: In relation to life satisfaction, ‘current yogic lifestyle’ showed a stronger association with the domains of ‘spirituality’, ‘health’, ‘standard of living’, ‘achievement’ and ‘feeling part of community’. Weaker associations were found with satisfaction with ‘relationships’, ‘safety’ and ‘future security’. The domains of health, spirituality and community showed a lower level of satisfaction during the first year of Yogic Studies (YS1a and YS1b) than reported by those attending a weekly class, but those in their second year (YS2a, Ys2b) reported higher levels than those attending a weekly class.

As the measures were taken at the commencement of the modules, the lower scores for YS1a may indicate that students come to Yogic Studies with a lower level of life satisfaction than those in the community and may look to yoga to provide life meaning. The particularly low score on satisfaction with feeling part of the community may indicate some degree of alienation from mainstream society. The higher scores recorded by the commencement of YS2b may suggest that the adoption of a yogic lifestyle has improved their satisfaction with their health and that yoga is meeting their spiritual needs as well as a sense of community.

The role of relationships in wellbeing: Satisfying personal relationships are seen as an essential determinant and a necessary condition for fulfilment and life satisfaction. Participants in this study quoted positive relationships (with partner, family, friends) most frequently as an essential factor in their wellbeing. The results of this study indicate that adoption of yogic lifestyle shows only a low correlation with satisfaction with one’s personal relationships. The particularly low level of satisfaction for YS1b (mean = 6.0) may suggest some level of disruption of relationships at this stage of the course. The results may indicate that the wellbeing associated with a yogic lifestyle may stem from change in self-acceptance and an inner contentment rather than satisfaction derived from relationships. This may reflect a shift from an external focus to an internal focus for wellbeing. Further research on the connection between yogic lifestyle and relationships would be useful.

Relationship between yogic lifestyle and perceived control: The hypothesis regarding the positive relationship between yogic lifestyle and perceived control of internal states was supported by the moderate correlation (0.43) between the two, similar in size to the relationship between yogic lifestyle and wellbeing. When the scores for perceived control, satisfaction with achievement, spirituality, current yogic lifestyle and satisfaction with life are mapped on a common scale (% of scale maximum), they show increasing coherence with progression through Yogic Studies. As the development of self-awareness and self-acceptance is a major feature of a yogic lifestyle, this finding adds support to the possible mediating role of perceived control in the maintenance of a sense of wellbeing and its connection with the Eastern spiritual tradition of self-acceptance.

Conclusion

Adoption of a yogic lifestyle was moderately correlated with measures of SWB. Students undertaking an intensive Yogic Studies course showed higher self ratings of yogic lifestyle than those attending a weekly yoga class. The adoption of a yogic lifestyle was more strongly associated with frequency of personal yoga practice than yoga class attendance and showed little association with the number of years of practising yoga. Students in their second year of Yogic Studies showed higher levels of life satisfaction in the domains of spirituality, health and community than those attending a weekly class, but first year Yogic Studies students had even lower levels of satisfaction. Although reported by participants as the most important factor in their wellbeing, yogic lifestyle was not associated with improved satisfaction with relationships.

References

Berger, B. and Owen, D. (1992) Mood alteration with yoga and swimming: aerobic exercise may not be necessary, Perceptual and Motor Skills 75 p 1331–1343

Bhushan, L. (1998) Yogic Lifestyle and Psychological Wellbeing, Yoga, Sivananda Math, Munger, India May 1998

Cohen, M. and Penman, S. (2004) Yoga in the West: Beyond exercise, beyond therapy, Vyerti Conference, Melbourne

Cousins, R. (2001) Predicting Subjective Quality of Life: The contributions of personality and perceived control, D. Psych Thesis, Deakin University, Melbourne

Cummins, R. et al (2001) The Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Survey 1, Report 1, Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University, Melbourne

Cummins, R. et al (2002) The Australian Unity Wellbeing Index Survey 4 Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University, Melbourne

Cummins, R. (2004) ‘The Wellbeing of Australians – Personal Financial Debt’ Survey Report 11, Australian Centre on Quality of Life, Deakin University, Melbourne

Diener, E. (1997) Recent Findings on Subjective Well-being, Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology, March

Diener, E. (2003) Subjective Well-being is desirable, but not the summum bonum, Paper presented at Uni. of Minnesota Interdisciplinary Workshop on Well-being, Oct 2003

Eckersley, R. (2004) Beyond Happiness, InPsych, Bulletin of Australian Psychological Society, October 2004

Feurstein, G. (1975) Textbook of Yoga, Rider and Co, London

Lu, L. (1999) Personal or environmental causes of happiness: a longitudinal analysis, Journal of Social Psychology, Feb 1999 Vol 139, issue 1

Neill, C. (1999) The role of personal spirituality & religious social activity on the life satisfaction of older widowed women, Sex Roles: A journal of research, Feb 40(3–4)

Nespor, K. (2001) Yoga and mental health. Course for Yoga teachers, Gasslingsbo, Sweden.

Netz, Y. and Lidor, R. (2003) Mood alteration in mindful versus aerobic exercise modes, The Journal of Psychology, 137(5) p405

Pallant, J. (2000) Development and Validation of a Scale to Measure Perceived Control of Internal States, Journal of Personality Assessment, 75(2): 308–337.

Personal Wellbeing Index, Version 3 (2005). The International Wellbeing Group http://www.deakin.edu.au/research/acqol/instruments/wellbeing_index.htm

Ryan, R. and Deci, E. (2001) On Happiness and Human Potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic wellbeing, Annual Review of Psychology, 52: 141–166

Ryan, R. and Deci, E. (2000) ‘Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development and well-being, Am. Psychol., 55: 68–78

Ryff, C. D. and Keyes, C. L. (1995) The structure of psychological well-being revisited, J Pers Soc Psychol., 69(4): 719–27

Ryff, C. D. & Singer, B. (1996) Psychological well-being: Meaning, measurement & implications for psychotherapy research, Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 65, p 14–23

Schumaker, J. (1998) Can religion make you happy? Free Inquiry, Summer, 1998 Vol 18, No 3