Addiction - A Systems Approach (Issues for Yoga Teachers)*1

Mahima Price and Gillian Hand (Sannyasi Mahimananda and Sannyasi Kriyamurti), Australia

Our workshop looks at the broad nature of addiction and issues which may arise for yoga practitioners and teachers when approaching addiction in this way. For a long time many have tried to understand why intelligent sensitive people seem to abandon self-care and responsibility, and social responsibilities, and hand over their health and happiness to an addiction. Over the years, religious thinkers, medical researchers, and behavioural and social scientists have come up with ideas which throw some light on this perplexing subject.

We will talk about these thoughts by looking at the development of the diagnostic and treatment models/theories used in Australia and other 'western' countries. We will go through these models in an historical progression to see what they say about the nature of addiction, what observations have been made redundant by subsequent ideas, and what each model says that is relevant today.

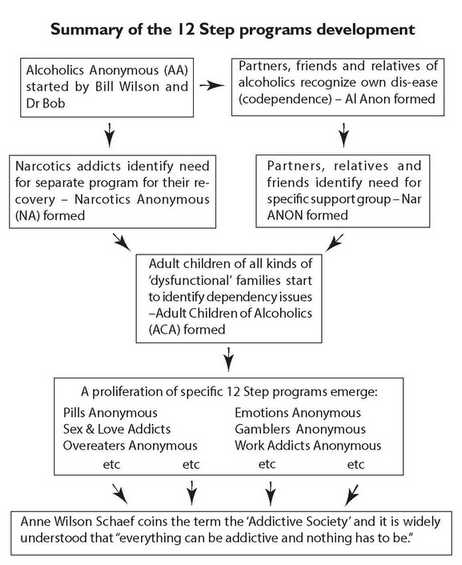

As the diagnostic and treatment models developed, a parallel process has occurred with the development of the myriad Twelve Step recovery programs, from Alcoholics Anonymous in the 1930s in America to well over one hundred different Twelve Step programs assisting millions of people globally in 2000. This phenomenal expansion reflects the deepening understanding of the nature of addiction. This is vital for us to comprehend if yoga is to support people in achieving and maintaining sustainable recovery from addiction, and, if it is to be an integral part of realistic prevention programs.

Western diagnostic and treatment models

A model is a way of classifying or defining a problem or situation so it can be understood and communicated to others. What is important to remember is that a model also defines a 'mindset'. It tells us what people who adhere to that model believe. In this case, what they believe relates to the nature of addiction. What has been highly visible for a long time is addiction to things, especially drugs, illegal ones and the legal ones like tobacco, alcohol and prescription drugs. An historical overview of the models reveals the progression of beliefs and 'mindsets' that people (and society) have developed to explain addiction and to underpin their prevention and treatment decision.

Moral model

This theory first gained precedence to explain alcoholism. Lawmakers, the medical establishment, religious leaders and the partners, parents and colleagues of alcoholics could only make sense of their perplexing behaviour by seeing it as a moral problem. They came to believe that it was a matter of lack of 'moral fibre', an innate lack of decency. This became the mainstream belief, no matter how upstanding the drinker might have been in the past or when sober.

This view was incorporated in the legal system. This 'lack of morality' was defined as a crime. Therefore, alcoholics were punished. They could be incarcerated in prisons or in lunatic asylums. This way of seeing addiction also 'shamed' the alcoholic by stating that if they simply decided to be a moral person they would be able to control alcohol. This meant that being unable to stop drinking, or relapsing into destructive drinking, was seen as proof of character weakness. People sat in judgement, seeing the alcoholic as 'beneath them'.

This is no longer the 'official' view of addiction and addicts. However, it still has wide currency in stereotypes of alcoholics/addicts and the prejudices held towards them. We often see these moralistic perceptions affirmed and strengthened in the media. The moral model is still enshrined in today's legal system, especially in the current trends of zero tolerance and mandatory sentencing.

Disease model

A new belief about the nature of addiction emerged in the 1930s with the establishment of Alcoholics Anonymous (AA). People who subscribe to this model believe that addiction (to a 'drug of choice' – alcohol in the case of AA) is a disease which is progressive and leads to insanity and death. They believe the disease is incurable, but can be arrested by remaining abstinent from the 'drug of choice' (or process of choice) one day at a time.

Dr Silkworth, an early advocate of AA, said that alcoholism was caused by an allergy to alcohol coupled with a compulsion to drink it. Recent research into genetics and the physiological and pharmacological processes of drug tolerance and withdrawal lends weight to this notion.

The medical model is a derivative of this understanding of the physical component of the disease model in relation to substance addictions. This led to them being treated within a medical framework. Medical interventions and treatments have been established which utilize various medications. Some current examples are medicated detoxification, and the pharmacotherapies like the methadone program, Naltrexone and Campryl etc.

These treatments are very appropriate for some people for some time, especially when the patient is at risk of self-harm or death, or of engaging in criminal activity to acquire alcohol or drugs. I feel that the medical model is most successful when it is part of an overall treatment plan that utilizes other models in an holistic manner. Alone, it tends to be symptom specific and focused on maintenance rather than sustainable change.

The disease model has continued to evolve other insights into the nature of addiction. Bill Wilson, an alcoholic and one of the two founders of AA, was 'freed from the compulsion to drink' as a consequence of a spiritual experience. He believed that alcoholism was a 'spiritual dis-ease' born of 'spiritual bankruptcy'. Carl Jung expressed the view that the alcoholic was looking for the spirit in the wrong place and that the only hope for lasting recovery was for the alcoholic to experience something akin to a 'conversion experience' in content and intensity.(2) People who subscribe to this interpretation of the disease model believe that sustainable recovery from addiction is achieved by developing a spiritual way of living. They do this by practising the Twelve Steps of recovery. (We have yet to research the origins of the Twelve Steps. The generally accepted story is that the steps came to AA via the Oxford group of the Theosophical Society, who developed them by systematizing teachings of the rishis of India.)

Over the last 20–30 years, coinciding with the development of popular psychology, the disease model gave rise to a new interpretation, the notion of dis-ease with oneself, and the world. Simply put, subscribers to this belief explained addiction as a form of self-medication, in order to ameliorate or numb 'a lack of ease' or 'psychological' pain. This self-medicating 'solution' to the dis-ease becomes a problem in itself because the 'relief' diminishes as the compulsion to drink/use becomes an addiction.

This dis-ease with oneself and lack of ease with life is seen to be what causes abstinent alcoholics/addicts to relapse, or take up another addiction, e.g. a different substance or a process addiction like workaholism, gambling, codependence. In this context, the Twelve Steps are used as a personal growth process.

Psychodynamic model

Western psychology has developed insight into the causes of 'dis-ease' with oneself/the world and the consequent self-limiting beliefs and self-destructive behaviours. It developed a vocabulary with which to identify dysfunctional processes and facilitate changing them. The psychodynamic model is based upon these insights and processes. People who subscribe to this model believe the nature of addiction lies in self-medication of psychological distress which is the legacy of childhood trauma. The word trauma here relates to a wide range of occurrences, as well as 'lacks'. It relates to the things we associate with the word trauma, like the death of someone significant, being lost, abused etc, and to the absence of parental care expressed in physical and/or emotional neglect. The model also recognizes 'not so visible' trauma created by events that are traumatizing in the way they are perceived by that particular individual. Other 'traumas' are the result of specific developmental needs not being filled, the consequence of which are uncomfortable/painful 'frozen needs'.

These 'traumas' are sometimes accessible to the conscious mind and therefore remembered. More often they are lodged within the individual's unconscious mind. This means that they, and their resultant beliefs and behaviours, persist until some type of psychological intervention occurs. In the meantime, the distress/pain continues, and so self-medication can bring temporary 'relief'. The more often a person self-medicates the less they develop coping skills, and so they enter a never ending spiral. A further complication is born when the body develops a 'tolerance' to the substance used to self-medicate, so the person must take increasing doses in the attempt to get the same effect. The body 'adapts' to some substances and when its use is stopped the body registers distress known as withdrawal or 'hanging out'. We can see again that the 'solution' becomes another problem.

Those who subscribe to the psychodynamic model believe that there is a treatable individual psychological component in addiction. Their treatment programs involve processes which assist the person to identify and heal this component. The assumption is that this psychological healing removes the reason for substance and process abuse and, therefore, the underpinning of the addiction is removed.

Psychosocial model

This model integrates the insights developed within the field of psychology, (especially cognitive-behavioural psychology) and the observations of the developing field of sociology. This model identifies the nature of addiction as an interaction of individual learning, and the social forces impacting upon the individual. People who subscribe to this model believe that addiction is behaviour which is learnt and then affirmed and reinforced by the person's environment. In this context the environment includes: the family, peers, school, subculture and dominant culture. It is not just what a person might 'learn' as they 'make sense' of trauma etc, but what they learn from what they see and hear around them. If they observe that substances or particular activities are used as a way to control stress, then they will do the same. If substance use, gambling etc. are advertised as the best way to have a good time, or look 'sophisticated', then they will learn that they are only OK if they are doing these things. They also learn in a covert way that their self-esteem is dependent upon consuming or acquiring, or having a partner, or by appearing to be helpful to all etc.

Addiction is born out of the habit they acquire by consuming substances, obtaining objects, doing certain activities or fulfilling a certain role, because a positive sense of self cannot be sustained by externals alone. The sense of 'OK-ness' accrued in this way is fleeting, therefore, the person engages in these substances or processes repeatedly in the attempt to feel OK about themselves. Because their self-esteem does not stay high, they believe the lack of lasting feelings of 'OK-ness' is their fault and so they try harder. A lot of these beliefs are reinforced to serve the ends of an economic system which requires increasing consumption to remain buoyant. This is serviced by the advertising industry.

Another aspect of this model relates to the beliefs and behaviours children learn from their parents. Educators have known for a long time that children learn most effectively from what they see 'role-modelled' rather than from what they are told. Advocates of this model maintain that what is learnt can be 'unlearnt'. Prevention and treatment programs promote a cognitive understanding of what the individual has learnt. With support, the person sorts through their knowledge and skills to decide what is useful and what impedes the type of lifestyle they seek. They then relearn and/or acquire new knowledge and skills with which to develop and maintain new behaviour, e.g. abstinence. This new learning can be both cognitive and experiential.

Socio-political model

Growing awareness of the system of power structures within 'western' societies began to be articulated with the further development of the social sciences. Marxist and later feminist scholarship underpinned another sociological model based upon understanding systemic disempowerment. Those who adhere to the socio-political model believe social inequity is a contributing factor to addiction. They believe that those who have less opportunity and are consequently excluded from the 'rewards' of the secular materialist culture are more likely to become addicted to substances and processes. As money, outward success and its 'status symbols' are the building blocks of self-esteem in this system, lack of money and lack of opportunity to 'succeed' promote low self-esteem and frustration. The individual seeks temporary 'pleasures' as compensation or as self-medication against the emotions provoked by the sense of missing out and the harsh realities of poverty and discrimination. Once again addiction can result as the 'solution' becomes the problem.

Advocates of this model support social change as a means of prevention. They support disempowered and marginalized groups to develop the skills and networks to become more self-determined. They may support the maintenance of traditional cultural values that determine the respect and esteem of an individual by means other than material acquisition.

The moral model said that the cause of addiction was the individual's lack of morality. (Individual.) The disease model said, “Oh no, it's not a moral weakness, it's a disease which can be arrested.” (Individual.) The psychodynamic model says, “No, it's not the individual, it's the emotional shaping by family and by trauma/neglect in early life.” (Individual and family.) The psychosocial model says, “Well, that may be true, but it's also what they were taught about themselves in the world, the patterns, labels and expectations.” (Individual, family, school, peers, advertisers.) And then the socio-political model is saying, “Well, all of that could be true, but all of them are affected by the power relations in a society which determine who is powerful and who is systematically marginalized and disempowered.” (Individual, family, school, peers, advertisers and the whole social structure.)

The idea of 'what is the nature of addiction' is getting bigger and bigger! By the 1980s it was so big that governments (in Australia in 1985 and 1999) said, “Substance use in our society is inevitable. Let's concentrate on minimizing the harm it does.” So they developed the public health model.

Public health model

This approach was developed to provide an integrated approach which took into account the effects of the different substances, the social and psychological aspects of the user and the sociological context of their use. The focus of this approach reflects the belief that nothing can be done to eradicate substance abuse itself and, therefore, resources are better utilized in an attempt to stop use becoming abuse and also to minimize substance-use related harms to drug-using individuals and to society at large. Advocates of this model utilize mass media to run campaigns aimed at halting the progression/minimizing the harm.

Some examples of these in Australia have been: television advertising aimed at convincing teenagers to 'stay in control' of their drinking by educating them about the 'safe levels' of alcohol consumption and engendering the idea that it is 'uncool' to drink excessively and vomit etc.; random breath testing by police and the arrest of people driving over the 'safe' level of alcohol consumption; needle and syringe exchanges where intravenous drug users can get clean needles, which minimizes the harm caused by needle sharing and the spread of HIV and hepatitis C; methadone maintenance, which keeps heroin addicts on methadone for long periods to minimize the risk of engaging in criminal activities to acquire heroin.

Community development and community education are also key strategies in this approach. (The individual, family, schools, peers, advertisers, power relations … and the whole society believing addiction is an inevitable feature of our culture!)

THE ADDICTIVE SOCIETY

As you know, and as Mahimananda has so fully described, the nature of addiction has been under consideration for many years. We are always looking for ways to understand the behaviours, thoughts and feelings which seem to characterize addiction so that we can find solutions which might help to improve lives which seem to be controlled by these seemingly unbeatable forces. As just discussed, models of dependence have been named and various approaches have developed over a period of time. All have their useful and not so useful aspects. As these models have been developing, thinking can also be charted via the progression and development of the Twelve Step recovery programs.

Firstly, Alcoholics Anonymous (AA) was started as a desperate attempt to help alcoholics. It was started by Bill Wilson, who was a self-identifying alcoholic. He believed that the best way to have any impact on his battle with alcohol was to meet with others who were also struggling in this way. He felt that by supporting each other and naming the commonly experienced thoughts, feelings and behaviours, plus devising and sticking to a predictable program based on spiritual concepts and practical suggestions, each person could share experience, strength and hope, within the structured context of a meeting, and thus achieve and maintain sobriety. The meetings had a specific foundation of twelve steps and traditions which were carefully followed. These steps were supported by regular readings from clearly written texts and the meetings always closed with the Serenity Prayer: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things that I cannot change, courage to change the things I can and the wisdom to know the difference.”

It took a while for the originators to gain group members and to stabilize the program. However, once established the Twelve Step program became extremely successful and is still seen as one of the more viable options available today.

After a while, as alcoholics began to get sober, and stay sober (because, of course, many had been stopping and starting for years, trying to beat the influence of alcohol), their partners, friends and relatives began to notice some degree of discomfort in themselves. They were used to someone who was mostly totally focused on getting the next drink, which meant that the non-alcoholic usually made most of the decisions, tried to pay the bills, tried to keep the disgraceful behaviours safely confined, made excuses for the alcoholic, cleaned up after the alcoholic, and generally controlled and took care of things. This was a predictable role which, whilst not exactly pleasing, gave some meaning and purpose to life, made a certain amount of sense out of chaos and provided a sense of being needed. It also provided quite a bit of drama – albeit negative drama.

As the alcoholic recovered, and began to take more control of his/her life, the partner/relative/friend would begin to experience a strange sense of unease – and perhaps also loss. The alcoholic was always at meetings, or talking to other alcoholics and helping them in the recovery process. They were also beginning to want more power and control within the relationship. Even though they had exerted a great deal of control during their drinking days, simply by the very nature of their actions, this was different. The recovering person was expecting to consult over decisions, to be treated with respect and was altogether assuming their rightful role within the relationship. This left the non-alcoholic without the predictable role they were used to – and a lot of accompanying distressing feelings, most especially the feeling of not being needed in the ways they were used to.

Many of these partners knew each other, since their partners were friends in AA. It was natural that they would have the idea of starting their own meetings to help themselves recover from what they had come to recognize as their own disease. Thus Al-Anon was formed by Lois, the wife of Bill Wilson, one of the founding members of AA.

For some time, these were the only Twelve Step recovery programs available and many people were helped by them. Then, as illegal drugs became more prominent, and users were needing to recover, they felt that some of their issues were too different from those of alcoholics. For example, cost and availability of their drugs, what they had to do to get them, different rituals associated with using them etc. There was a need to identify more closely with other drug addicts. The main success of the Twelve Step programs can be attributed to a sense of identifying with the others in the room and a feeling of belonging and being understood. And so Narcotics Anonymous (NA) was formed. Again, the experiences of those living with the legal implications and ever-present threat of overdose and death, which accompanies use of certain drugs, means that the identification process within meetings is different. Thus Nar-Anon began for those people in relationships with drug users.

Then in the late 1970s people started to say that they had experienced both sides of the coin. They were addicted to both SUBSTANCES and PROCESSES. Some called themselves 'double winners'. Through speaking and identifying, they came to realize that most of them had grown up in 'alcoholic (or otherwise dysfunctional) families'. Thus Adult Children of Alcoholics, commonly referred to as ACA, was founded.

| Substances | Processes |

|---|---|

| alcohol | relationships/roles |

| illegal drugs | work/activity |

| presciption drugs | gambling |

| smoking | power & control |

| food | sex/love |

| caffeine | spending/shopping |

| steroids | exercise |

| TV |

Some characteristics of addiction

- Dishonesty (denial projection, delusion)

- Not processing fellings in healthy way (distortion, frozen feelings, holding onto fellings, etc.)

- Need to control

- Thinking disorders (confusion, ego-orientation, obsessive thinking, over reliance on logic, analyzing, linear thinking, etc.)

- Perfectionism, inferiority/grandiosity

- Rigidity, stasis, negativism

- External referenting, attention seeking, approval seeking

- Judgementalism

- Fear, depression, self-centredness

- Loss of personal morality (compromised value system - loss of spiritual base)

I was part of this groundswell in Sydney, Australia and it was amazing how many people identified in this way. People were talking about how out of control they felt and how this spread into all areas of their lives. They felt that they had not learned how to live their lives with any degree of self-monitoring or self-discipline and did not know how to relate to others. They especially did not know how to take care of themselves nor how to be comfortable with intimate relationships. Their growing up experiences had been a mixture of severe control or total abandonment, and they had no idea how to be balanced. The Twelve Step programs offered the company of others who felt the same and who were using a set of steps and traditions to provide the essential guidelines for living and, most importantly, a spiritual framework was the foundation of the whole program. This provided access to something greater than the personality, self or individual and a sense of belonging in the greater scheme of things. Many people I know also began yoga at this time, as a way of embodying and amplifying these spiritual principles.

As the ACA movement grew, people began to feel the need to identify with some very specific forms of addiction and so a large number of other Twelve Step groups emerged. These included Pills Anon, Overeaters Anon, Sex/Love Anon, etc., etc. As this continued, the theorists were busy trying to make sense of this proliferation. It seemed that just about anything could be named as an addiction, and how could this be so?

Eventually an American psychotherapist, named Anne Wilson-Schaef*3, came to understand that because of the way society was and is functioning, it was almost impossible to escape developing as an addicted person in some way. Society (as she saw it) actually inculcates, conditions, condones, even requires that a person be addicted in order to belong – to be part of society as we know it. She coined the phrase 'the addicted society' and it is this concept which we are using as our basic premise for this workshop.

Some characteristics which could commonly be used to describe the 'addicted society' are dualistic thinking, dishonesty, obsessive thoughts, feelings and behaviour, controlling, manipulating, interpreting/assuming, self-neglect, comparisons, blaming/shaming, jealousy, consumerism, accumulating money, thrill seeking (the easy high), worrying, lack of balance, external locus of control, speediness, constant need for sensory stimulation. I just want to look at two examples to demonstrate our theme.

- Dualistic thinking: By this we mean viewing the world in terms of opposites which must always be in direct conflict with each other. There is no room for the possibility that two differing views can both be acceptable – or that perhaps even other alternatives may also exist, which are also OK. Some examples are: in/out, win/lose, right/wrong, us/them, for/against. This thinking is an oversimplification but it provides us with the illusion of control over a world which is actually constantly in process. We feel forced to choose between two options and we think that if we can make the 'right' choice we can belong and therefore be safe. But safe from what? Safe from the processes of change perhaps? Or safe from the reality that we cannot know what each new moment will bring?

- Self-centredness: In the 'addictive society' the self is central and self-centredness is seen as a virtue. It is accepted and even encouraged. Whilst on the surface we are taught to pay attention to the needs of others, the unspoken message is that if we seem to be doing that, then others will take care of our needs. In other words, our caring for others has the ulterior motive of making sure we get ourselves taken care of. There is nothing unconditional about this. We are taught to hoard our belongings, protect our homes and only give out as much as we expect to get back. There is no concept of each being a part of a 'whole'. There is no understanding that the 'whole', being composed of each part, must automatically be affected by anything which each part does, because each part is in relationship to, and belongs to, the whole.

Jeff Moss, an Australian addiction specialist, developed this way of looking at the issues we have raised. He called it 'the Addiction Iceberg.*4 We all know that one third of an iceberg is visible above the waterline, likewise it is addiction to substances that has been most visible until very recently.

YOGIC HOLISTIC MODEL

What Kriyamurti has just described about the addictive society is the 'lowering of the water level'. It enables us to come out of denial about the nature of addiction. Believing that it's just alcoholics or 'junkies' that are addicts allows people to say, “I'm not like them. I don't drink or use drugs like a park bench drinker or a junkie shooting up in a public toilet and committing crimes to support their habit.” Or, “I don't have the problems they do. I don't come from the same socio-economic class/cultural/disempowered group as them.” Or, “I don't drink/use drugs at all so I am not an addict.”

The development of the multiplicity of Twelve Step recovery programs has allowed us to see that which was once only dimly visible. It is called 'process addiction'. This is an addiction to things in the shape of activities and objects. Recent research suggests that some or all of these may have a biochemical foundation in the sense that they stimulate certain brain chemicals/hormones. We look forward to further research findings in this area. What we do know at present is that the repetition of activities becomes an addiction when it becomes an external 'locus of control', and the repository of unsustainable self-esteem. The same is true of objects. Jeff Moss has described this in the second level of his addiction iceberg.

As you can see by looking at that huge area right at the bottom of Moss's addiction iceberg, it gets 'worse'! The Twelve Step recovery programs, Al-Anon and Adult Children of Alcoholics (ACA) and other 'dysfunctional families', and other tools like psychological testing, have established that it is possible to be addicted to people (roles and dynamics). Oh surely not! I hear you say? Surely experts/clients, leaders/followers, couples, parents/children aren't all addicted to each other?

The answer is yes and no. An example of yes is, if a leader is addicted to exercising power, the follower cannot function without a leader and becomes addicted to the leader. Their 'locus of control' is in the leader, and the leader's 'locus of control' is in whatever and whoever will give him or her power in that moment. I'd like to talk about the no a little later.

Our search for the nature of addiction has led us to theories and beliefs that are incredibly big! We have some good news and some bad news. The bad news is – “everything can be addictive!” The good news is – “nothing has to be.”*5 What makes the difference? Something is addictive if it establishes and reinforces three things. The first is the external locus of control. This can be illustrated by saying the addict is a puppet and the substance, object, activity or process pulls the strings. The second is negative outcomes for the addict in the medium to long-term. The third is the system and patterns of thought which strengthen and maintain the first two components. So, the difference is made by:

- the development of an internal 'locus of control'.

- the building of positive, sustainable and sustaining short, medium and long-term outcomes which empower an individual and underpin healthy self-definition and esteem.

- developing and practising systems and patterns of thought which result in the other two, as well as allowing for change and growth.

As we follow the development of the diagnostic and treatment models to date, we conclude that addictions are social and cultural. If we believe Ann Wilson Shaef, Jeff Moss and many others, we conclude that everything can be addictive and that everyone can become addicted. If we follow the development of the Twelve Step programs, we find they have multiplied to cover all types of addictions.

What we want to suggest is that all these addictions to substances, process, objects, activities, and people are not separate addictions but the manifestation of addiction (singular) from within an addictive system, an addictive society.

So, why is it so important for us as yoga teachers and practitioners to know all this in order to teach asanas, pranayama, yoga nidra and meditation in schools as an addiction prevention strategy, in detox and rehabilitation programs for substance addicts, in treatment programs for process and people addiction, or even in community classes which inevitably include addicts of various types?

As well as having the yoga expertise to know which practices to teach for detoxification, liver damage, obsessive thoughts or stress management etc., we also need to realize that the student's symptom, or difficulty, is a consequence, and part, of a system. This is the basis of a 'systems approach' to the development of a yogic holistic model.

There are two major reasons why it is important for us to develop this model and approach. Firstly, if we don't fully comprehend the nature of addiction, we might assist our students in the cessation of certain symptoms, but then the maintenance of addiction merely manifests differently, e.g. giving up drugs but taking up drinking, or gambling, or entering into a codependent relationship etc. Also, by only addressing symptoms, and getting to the whole nature of addiction, we leave our students vulnerable to relapsing into their original drug or process of choice.

Secondly, we are people socialized within the same system, the addictive society. When we teach yoga in the addictions context we are attempting to be part of the solution to a problem in which we too are immersed. Therefore, no matter how well meaning, good-hearted and experienced we are there are serious limitations to our efficacy. We need to develop a philosophical base which is beyond our socialization, outside the addictive society. In adopting a yogic lifestyle we are already part of the way there.

This need for a wider perspective, this yogic holistic model, can best be described by utilizing a metaphor.

Spend some time finding a solution/ or solutions to the 'nine dot' exercise.*6 Now find the solution.*7 Check that you only have four lines and that all the dots are joined. If you have solved it, you will have an 'arrow' shape that extends 'beyond the square'. That is the point of this exercise. All our socialization will force us to see those nine dots as 'a square'. They are not. It is impossible to solve the exercise holding the belief that the dots are 'a square'. This exercise is often used to teach people lateral thinking. Its relevance to us is simply this, to help people achieve sustainable recovery from addiction we need to see the whole system (including ourselves). We need to draw on the strengths of 'the square', e.g. the models, the twelve step programs etc., but act from beyond its limitations.

A yogic holistic model incorporates all the information held within the models of dependence, Jeff Moss' work and Ann Wilson Shaef's 'addictive society' and articulates it from the yogic perspective, the place of creativity, balance and integration. The yoga of Patanjali has tremendous potential for a holistic response to addiction. It is 'outside the square' of the addictive society. The eight stages: yama, niyama, asana, pranayama, pratyahara, dharana, dhyana, samadhi, are: “The process and practical methods of raising levels of awareness, gaining deeper wisdom, exploring the potential of the mind and eventually going beyond the mind.”*8 They support an inner 'locus of control' within a context of union and connection. Equally important for the student/ addict in recovery is a yoga teacher who is a mentor and model, someone who has used yoga to heal the impact of the addictive society upon themselves in whatever way it manifests itself. Swami Niranjan raised this point when he asked us to look at our negative habits and our attempts to transform them.

Any yoga teacher who has not healed the impact of the addictive society upon themselves is still 'inside the square'. This is a situation where self-study becomes a pivotal resource in successfully applying a yogic holistic model to addiction. As we use yoga to heal and transform our negative habits and addictions, we will more fully know how to support this change in others.

Notes:

*1. Sannyasis Mahimananda and Kriyamurti are coordinators of the Satyananda Yoga Teachers Association (SYTA), Australia, Yoga and Addictions project, which was begun in 1999 in response to Swami Niranjanananda's request. The aim is to develop a holistic yogic model which addresses the nature of addiction within the framework of viewing all addictions as symptoms of the addictive society. It is hoped to achieve outcomes which include development, implementation and evaluation of both community-based yoga programs and training/professional development for yoga teachers - thus putting an holistic yogic model into practice. The project is comprised of two separate yet related lines of enquiry and action. The first relates to researching yoga principles and practices which are, or could be, utilized to assist people to recover from addiction. The second part of the project relates to developing input from the research of yoga principles and practices for teacher training and professional development. This workshop is the summation of progress to date and an indication of future direction. It is a 'concertinaed' version of three workshops developed and run, sometimes more than once, since April 1999.

*2. Reported in the writings of Bill Wilson.

*3. Anne Wilson Schaef, When Society Becomes An Addict, Harper & Row, San Francisco 1987.

*4. Diagram of iceberg from paper given by Jeff Moss at an addictions conference in Darwin, Australia 1985.

*5. Anne Wilson Schaef.

*6. The 'nine dot exercise' is found in standard psychological texts relating to the processes of perception.

*7. People experience difficulty solving this exercise if they perceive the nine dots have the shape of a square. If they believe the dots form the square they can assume that the exercise must be solved within the confines of 'the square'. This is not one of the instructions and the solution to the exercise relies upon seeing beyond the bounds of 'the square' and the unconscious decision to allow it to define the parameters.

*8. Swami Satyananda Saraswati, Four Chapters on Freedom, Bihar School of Yoga, Munger, Bihar, India, 2nd Australian edn, 1980, p. ii.