Yoga: An Instrument of Psychological Transformation*1

Dr L. I. Bhushan (Sannyasi Yogasindhu)*2

As a science of health, yoga hardly needs any introduction today. Its practices, particularly those of raja yoga and hatha yoga, are in wide use throughout the world and have been found to be effective as curative and preventative measures against several chronic and serious diseases. The modern principle of psychosomatics was conceived of in yogic literature thousands of years ago. It held that disease germinated in the mind and later manifested in somatic symptoms. Today medical science admits that most of our diseases are psychosomatic in nature. Disease originates from mental stress causing imbalance in the neurophysiological and endocrinal systems, resulting in psychosomatic disorders. These disorders again cause anxiety and other psychological symptoms popularly known as DIAFS (Disease Induced Anxiety & Fear Syndrome). Thus the mind-body interaction serves as a chain of cause-effect relationships to produce psychosomatic and somatopsychic symptoms. For their proper treatment, therefore, somatic or psychological management alone is not sufficient. The practices of yoga are effective because their approach is psycho-somato-spiritual.

Yogic psychology models

Although in modern times the prime reason behind the popularity of yoga has been its therapeutic use, yogic methods were not originally developed as curative techniques for different diseases. They were conceived as sadhanas (spiritual practices) for living a healthy and happy life without desiring material riches. In fact, yoga is a science of consciousness of which the mind is a part. In yogic literature, consciousness has different forms; it may be sense consciousness, intellectual consciousness or transcendental consciousness (Swami Satyananda, 1980). The first level of consciousness, called jagriti, is concerned mainly with sense awareness and interaction between the self and the world of name, form and idea. It is similar to what psychoanalysis calls the conscious level of mind. The next level, similar to the subconscious, is swapna, in which there is awareness of the manifest and the unmanifest. Third is the deeper level of nidra, which has been said to be a stage invisible within, also called shoonya. These three levels of consciousness are found in everyone. However, yoga also conceives of a fourth stage, turiya, which is an expanded state of consciousness. It is also called the superconscious mind which operates even without the aid of the senses. Yoga prescribes methods and sadhana to attain and experience the self-luminosity of total consciousness, where one becomes the observer, the drashta of past, present and future. Thus, yoga studies and analyzes different forms of consciousness and also provides methods to develop and experience its altered states and expansion.

Patanjali's Yoga Sutras is the first systematic text on yoga psychology in which yoga is explained in terms of controlling and managing the vrittis, or modifications of the mind. Yoga holds that it is the chitta vrittis which create problems and cause disturbances in the mind. By exerting proper control over the chitta vrittis, the individual succeeds in eliminating negative thoughts and feelings, develops a harmonious personality and acquires equanimity. Thus the mind is a central theme of yogic study.

Yogic techniques enable the practitioner to become master of his mind, rather than a victim of his emotions and desires. A description of vrittis shows that the modern cognitive approach to life was well understood in yoga psychology. Patanjali has mentioned five sources of vrittis: (i) pramana – proof or valid cognition, (ii) viparyaya – illusion or invalid cognition, (iii) vikalpa – fancy or objectless verbal cognition, (iv) nidra – sleep or absence of distinct cognition, and (v) smriti – memory or mental recollection of past cognition.

When these vrittis are related to narrow personal gains and losses they become sources of affliction or pain, called klista vrittis. However, when they are transformed into positive and spiritually oriented tendencies through yogic practices, they become aklista vrittis, which lead to lasting happiness and satisfaction. Patanjali has mentioned two broad methods of controlling the painful vrittis and transforming them into non-painful ones. They are: (i) abhyasa, or the practice of yogic methods, and (ii) vairagya, or the practice of detachment.

This resembles the modern cognitive approach, according to which our interpersonal problems are mostly due to faulty cognition, judgements and negative thinking. The solution lies in removing avidya (ignorance) by adopting a lifestyle of anasakti (non-attachment). Asakti (attachment) and vairagya (detachment) are the two extreme points on the same scale or continuum with anasakti being in between the two. Literally, asakti means 'narrowing the area of consciousness'. This leads to raga (lust), dwesha (hatred) and ahamkara (pride) which manifest as insecurity, possessiveness, aggression as well as mental and psychosomatic problems. Vairagya is the height of the nivritti (renunciate) way of life, which is difficult for normal householders to achieve. It is an ideal mode of life set by the saints and rishis. Yoga psychology prescribes anasakti as the path to enjoy lasting happiness and peace without being involved and disturbed by asakti. The asakti-anasakti paradigm presents a comprehensive and practical mode of mental health (Bhushan, 1994).

Among the yogic models of human personality, the principle of homeostasis runs central. It holds that any type of imbalance in the physical, psychological or pranic systems creates health and adjustment problems, and the cure lies in rebalancing them. All yogic methods emphasize how to restore physiological, psychic and pranic balance by removing toxins from the nadis (energy channels) and bodily systems, thus promoting health. The practice of hatha yoga has special cleansing and balancing effects on the body and mind and it awakens the nadis (Matthews, 1995).

In psychology we can trace the history of the study of individual differences to Galton, which is only 100 years back. However, thousands of years ago yogic literature described different types of human personalities and emphasized that the same yogic method was not suitable for all types of people. On the basis of temperament, four types of personalities have been described: intellectual, emotional, dynamic and mystic. Similarly, as per the mental state, the five personalities are: (i) moodha, (ii) kshipta, (iii) vikshipta, (iv) ekagra, and (v) niruddha. For each of these personalities different forms of yoga have been recommended. However, the most important classification is based on the three gunas of sattwa (harmony), rajas (activity) and tamas (inertia). These gunas are largely acquired and through them the desired transformation in attitudes and personality is possible through yogic practices.

Derivations and applications

- From the preceding discussion we can safely say that yoga has sound theoretical models which have withstood the test of time and scientific verification. The seers and saints of ancient India visualized what psychology has only come to discover towards the end of the twentieth century. Some of the concepts still need verification and investigation.

- Yoga psychology is both a positive and normative science. As such, it not only analyzes psychological processes and conditions but also sets the goal of evolution of mind. It prescribes methods for enjoying sound physical and mental health and for promotion of the self.

- Yoga has explained and revealed that real happiness does not lie in the acquisition of material gain and sensuous excitement. A mad rush for wealth and external stimulants ultimately results in frustration, agony, discontentment and personal, social tension. Real happiness lies within and can be achieved by caring for the spiritual aspect of self and living a life with transcendence and anasakti. This means extending love without expectation, widening the area of consciousness and ownness and experiencing enjoyment in giving to others and serving humanity.

- Yoga accepts the significance of such basic requirements and predispositions as ahara (food), nidra (sleep), maithuna (sex) and bhaya (fear), but emphasizes the role of samyama (self-discipline) in respect of their manifestations and fulfilment. This is illustrated in the first two steps of ashtanga yoga – yama (self-restraint) and niyama (inner discipline) – which are considered to be preliminary preparations of mind and conduct before beginning the actual practice of yoga. This saves people from indulgence in acts related to raga, dwesha and ahamkara.

- The yogic practices are based on a model of body-mind-spirit interaction. As such, they take care of the total being without overemphasizing or ignoring any of the three aspects. In raja yoga, for example, asanas and pranayamas are primarily somatic, pratyahara and dharana essentially psychological, and dhyana and samadhi predominantly spiritual. However, in every yogic practice all the three aspects, i.e. body, mind and spirit, are involved.

- Simple looking yogic practices have deep positive effects on the practitioner. Through their influence on the endocrine glands and the nervous systems, including brainwaves and blood chemicals, they purify and regulate the bodily systems and visceral functioning without any knowledge or conscious effort on the part of the practitioner. Transformation of the brainwaves in yoga nidra, regulation of melatonin secretions through ajapa japa and trataka, and cleaning of the coronary arteries with pranayama take place almost automatically, and the practitioner feels surprised as to how it happens. Similarly, a substantial reduction in depression, anxiety, psychotism, paranoid ideation, hostility, somatism, obsession, and intersensitivity has been found to result from living a yogic lifestyle (Bhushan, 1998).

- Last but not least in importance is the fact that yogic management of health and temperament is a method of self-help, without any induction of external chemical or metallic substances. It saves expenditure on medicine and surgery and adds to the patients' confidence and willpower, due to which they not only fight the germs of disease but also learn the art of living a confident and happy life. This strengthens the immune system of the body, which people in developed countries avidly desire, and saves money on treatment which the average person in developing and under-developed societies finds difficult to afford.

Yoga and the community

An important aim of community psychology is to meet the challenge of health hazards in community life. It is not only atmospheric pollution which causes health problems, rather our faulty and perverted lifestyle has also contributed substantially. Ornish (1990) has shown that coronary heart problems develop mainly because of faulty lifestyle. In Reversing Heart Disease he cites findings from over 300 cases recommended for bypass surgery and shows that their condition could be reversed by adopting a correct lifestyle and community living, without medication. The lifestyle included a simple vegetarian diet, certain yogic practices, a time schedule and collective or community living. In a more recent finding obtained from 250 Indian patients, Chhajer (1995) has confirmed the efficacy of yoga plus lifestyle in managing heart problems.

Medical experts quite often talk of balanced diet and natural living. However, the fact is that people in the higher strata of society, in particular, are more likely to live in artificial conditions and to consume rich and unhealthy food and drink. This habit has served as a false example of a status symbol for our developing society. People need to be educated about the yogic lifestyle which has its roots in our national culture. The yogic lifestyle includes eating simple, easily digestible food with two main meals and a light breakfast in the early morning. Dinner late at night should be avoided. The principle of 'early to bed and early to rise' should be practised. The day should begin with some physical exercise and yogic practices, and some time should be set aside in one's daily schedule for meditation and relaxation. The philosophy of karma yoga and anasakti yoga needs to be incorporated into one's daily interactions.

Indian community life in villages is nearer to the yogic lifestyle. Informal and cooperative living in rural areas provide emotional support and bonding for villagers and makes up for the non-availability of modern amenities. This way of life needs to be preserved and strengthened in spite of monetary cravings and political onslaughts. A concerted effort by social organizations and social workers is needed to develop greater informal and community feeling among people in urban areas in particular.

The practice of simple asanas, such as pawanmuktasana and surya namaskara, pranayamas and some relaxation practices needs to be introduced into our family life. This will act to prevent disease and to promote efficiency and the confidence in individuals to meet stressful situations quietly and comfortably. It has been seen that yogic practices weaken negative emotions and thinking and give rise to positive feelings. Transcendence, the key word in yoga, manifests in a feeling of 'we' and an expanded cognitive self. So the introduction of yogic practices in the family and community is expected to reduce violence and social conflict and to inculcate values of consideration and appreciation of others' views, which are so needed for the survival of our democracy. The recent 'yoga yatra', launched by Bihar School of Yoga in about 200 villages of Bihar and Gujarat, indicates that collective participation in yogic programs leads to diffusion of hostility and promotion of healthy interaction.

Yogic practices are most useful for children. Yoga experts advocate that actual yoga training for children should start at the age of seven years (Swami Satyananda, 1990) when the pineal gland is about to stop its secretion. Such practices are helpful not only for balanced growth but more particularly in the development of the intuitive faculty. Similarly, yoga training should find an important place in our educational system. Present day education has become job-oriented and has been reduced to vocational training. By incorporating proper yoga teaching in schools we would make education self-oriented which should be its real aim. To quote Swami Niranjanananda (1997), “Self-education is where yoga comes in: learning to channel the faculties of human personality, of human nature; learning to focus the mind, to have clarity of mind, concentration of mind; and learning to recognize the principles that govern a human personality in the form of strengths, weaknesses, ambitions and needs… In the ancient vedic tradition, at the age of eight, whether male or female, children were taught three things: the practice of surya namaskara to develop and maintain activity of thymus gland; the practice of nadi shodhana pranayama (alternate nostril breathing) to stimulate the pineal gland; and the practice of mantra (sound vibration) to increase concentration, to develop retention power and to develop mental tranquility.”

Introducing these practices and combining them with practices of visualization and awareness, such as breath awareness, yoga nidra, antar mouna or ajapa japa, are equally important for both children and adults. Bihar School of Yoga has worked out detailed courses of yogic practices for different age groups. Under its supervision about 300 children, both boys and girls, have been trained as anudeshaks (yoga teachers). They serve as child ambassadors for imparting yoga training to children in schools in various states of the country.

The findings reported by Selvamurthy (1993) highlight the promotive aspect of yoga. He has shown that six months of yogic practices conducted on junior defence officers produced “significant improvement in body flexibility, physical performance and also in cognitive and non-cognitive functions. The psychological profile revealed a reduced anxiety level, improvement in concentration, memory, learning efficiency and psychomotor performance. The biochemical profile showed a relative hypometabolic state and reduced levels of stress hormones. Studies of hypersensitive patients revealed the curative potential of yogic practices by a considerable reduction in stress responsiveness as well as restoration of baroreflex sensitivity”. Thus yogic practices are good intermediaries to promote psychomotor efficiency and personality.

Every society is confronted with tension and stress-related problems. The individualistic outlook, the mad rush for material gain and position, time pressure at work and role strains are some of the important conditions of the modern times causing stress, tension and psychosomatic and psychosocial problems. As per the yogic model mentioned earlier, avidya (ignorance) is at the root of various psychosocial problems. Avidya narrows and perverts our outlook and quite often we fall prey to suffering on account of asmita, raga and dwesha. If we analyze the prevailing social tensions and conflicts, we will find that either ego problems are at the base, or the need for possessions, material gain, recognition, power and supremacy, manifesting in symptoms of aggression, violence, suicidal tendencies and other sociopathic behaviour.

We cannot totally control or change the social scenario and situational conditions according to our desire, so a better way is to find out how best we can adjust to stressful conditions. Yogic techniques, including certain relaxing asanas, nadi shodhana pranayama and meditations such as transcendental meditation, preksha dhyana, yoga nidra, antar mouna and ajapa japa, have been found quite useful and effective in managing stress problems (Jangrid et al, 1988; Suryamani, 1990, Swami Satyananda, 1996).

In community life, satsang, devotional songs (kirtan) and dances based on bhakti yoga serve as useful tools in transforming cognition and promoting positive attitudes and emotions. Stressed patients have a lower level of melatonin discharge which is generally increased by meditation practices, resulting in a feeling of wellbeing. These practices are valuable as they cause simultaneous relaxation in body-muscles and mind with the added advantage of hypnotic suggestion.

Study report

The results of a study conducted under the guidance of Swami Niranjanananda (1995–96) on prisoners lodged in different jails in Bihar is worth quoting here. In 1995 a pilot study was done on a group of prisoners lodged in the Munger district jail. The participants were given one hour of yoga training, consisting of selected asanas and pranayamas in the morning, about 45 minutes of yoga nidra in the afternoon, and about one hour of kirtan, prayers and satsang in the evening led by sannyasins of the BYB Yoga Institute. After a fortnight the participating prisoners reported themselves to be physically and mentally fitter and less likely to fight amongst themselves or with jail authorities. The jail authorities also reported that the yoga program had been conducive to creating cordiality among the prisoners. It had also reduced the jail's expenditure on medicines and the jail environment had become friendlier.

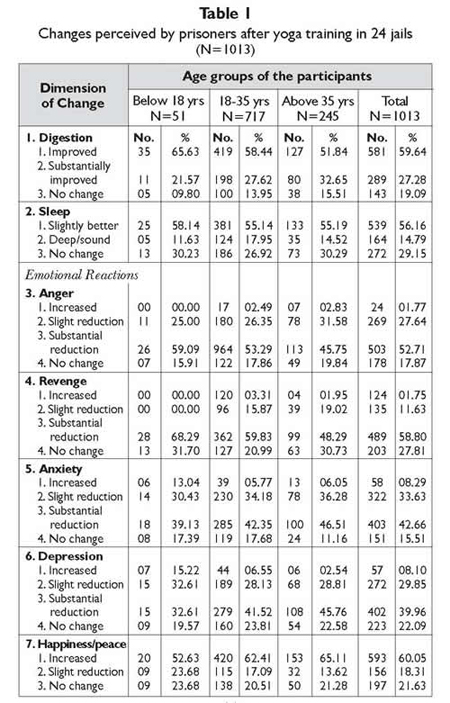

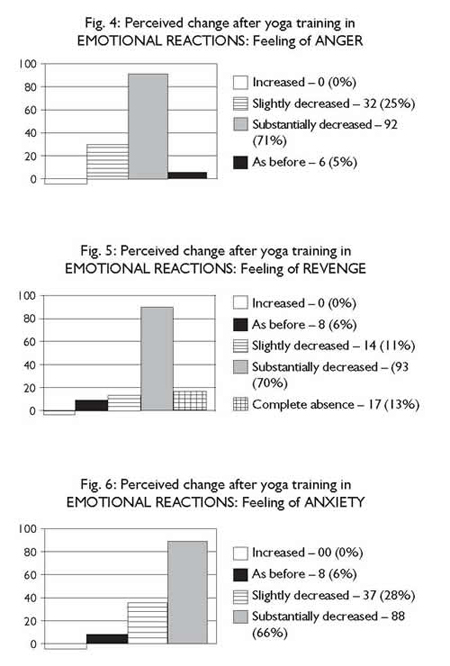

Acting on the report, the Government of Bihar agreed to introduce a yoga training program for prisoners in 24 jails of the state, including the central jails. A total of 1013 prisoners participated in yoga training programs of 15 days' duration in these jails. From the results obtained it was noticed that, after participation in the yoga programs, the prisoners perceived themselves to be physically fitter and more energetic, reported an improvement in digestion and sleep, and felt happier. They also reported a substantial reduction in negative feeling and emotions such as anger, revenge, anxiety and depression, and an improvement in happiness. 75.2% expressed a desire to perform altruistic acts and 63.11% to live a normal family and social life on their release from prison. Over 85% desired to continue with the yoga practices and to impart training to other jail inmates if the authorities so permitted. Details of the results are given in Table 1.

On the basis of the encouraging results obtained from the trainees and reports from the jail authorities, the Government of Bihar took a policy decision to introduce yoga training for the prisoners in all 82 jails of Bihar. As a first step, a Yoga Teacher Training Course was introduced in eight central jails for prisoners who were undergoing life imprisonment and had at least 10 years still to spend in jail. Selection of trainees was made on the basis of their choice and performance during the previous yoga camp. Altogether 172 cases were selected and trained for one month inside the central jails in 1996 by competent yoga sannyasins of Bihar School of Yoga. Of these cases, 167 passed the final examination and were awarded Yoga Teacher Certificates. Data available from 136 cases, presented in Figures 1–8, confirms and also indicates improvement upon the earlier results obtained from the 24 jails.

The results demand follow-up studies with improved tools and methods. However, they do indicate that yogic practices not only serve as curative and preventative measures against somatic problems, but also act as effective instruments of positive psychological and emotional transformation. It is hoped that governments and social organizations will come forward to make use of this instrument for the individual and collective wellbeing of people.

Notes

*1 Paper presented on 12 April 1998 as Dr Rajnarain Memorial Lecture during 3rd Biennial National Conference of Community Psychology Association of India, Varanasi.

*2 Dr L.I. Bhushan is Professor & Head, Dept. of Yoga Psychology, Bihar Yoga Bharati, Munger (India) & Ex-Professor & Chairman, University Dept. of Psychology, TM Bhagalpur University, Bhagalpur.

References

Bhushan, L. I. (1994), A yogic model of mental health. Indian Journal of Psychological Issues, 2, pp. 1–4.

Bhushan, L. I. (1998), Yogic lifestyle and psychological wellbeing, Yoga, 9 (3) pp. 30–40.

Chhajer, Bimal (1995), as referred to in 'Yoga and lifestyle management', Yoga, 6 (3) pp. 40–42.

Jangrid, R. K., Vyas, J .N., & Shukla, T. R.. (1988), Effect of transcendental meditation in cases of anxiety neurosis, Indian Journal of Clinical Psychology, 15, pp. 77–79.

Matthews, Shaun (1995), Balancing pitta dosha by using hatha yoga practices, Yoga, 6 (3) pp. 36–39.

Nagendra, H. R.. (1993), Holistic approach to the problems of modern life, in Yoga Sagar: Proceedings of the World Yoga Convention 1993, pp. 251–259, Bihar School of Yoga, Munger.

Ornish, D. (1990), Reversing Heart Disease, Ballentine Books, New York.

Saraswati, Swami Niranjanananda (1996), Yoga in Prisons of Bihar, Unpublished paper, Bihar School of Yoga, Munger.

Saraswati, Swami Niranjanananda (1997), Yoga and education, Yoga, 8 (6) pp. 1–15.

Saraswati, Swami Satyananda (1980), Yoga from Shore to Shore, Bihar School of Yoga, Munger.

Saraswati, Swami Satyananda (1990), Yoga Education for Children, Bihar School of Yoga, Munger.

Saraswati, Swami Satyananda (1993), Yoga Nidra, 2nd edn, Bihar School of Yoga, Munger.

Saraswati, Swami Satyananda (1996), Asana Pranayama Mudra Bandha, new edn, Bihar Yoga Bharati, Munger.

Selvamurthy, W. (1993), Yoga and stress management: A physiological perspective, Proceedings of the 80th session of Indian Science Congress (Part IV), Goa.

Suryamani, Swami (1990), Yogic Management of Stress, Bihar School of Yoga, Munger.